Non-Chinese people usually get Chinese names wrong. No, today I’m not talking about the pronunciation of the consonants zh and q.

Rant part 1: First names

In the US, people commonly ask you what your first name is, so that they can address you later. Starbucks ask for it to remind you when your drink’s ready. Lyft asks it for drivers to confirm the rider. This is considered the correct, polite and respectful thing to do. When the name of the individual isn’t familiar in the context culture, people usually follow up with a question, “how do you pronounce it”, to show a respect of the individual’s culture.

However, the problem spans further than just the pronunciation, aka the sometimes exotic mapping from spelling to sounds; the problem is that the existence of a first name is assumed. Quite often, however, it is the other case where it’s impossible to find a space-separated subsequence of one’s full name that they go by.

This has the same spirit as typesetting engines assuming text consists of space-separated words, or websites assuming all texts are written left-to-right, or Chinese sites forgetting that daylight saving times exist. The makes of said websites do not have bad intentions; it just does not occur to them at all that such assumptions might break.

The assumption of the first name is that (ordered by prevalence, highest first):

- Every individual has a name that they go by, and

- They prefer to be addressed in speaking and writing with this name (e.g. “Hi Alice how’s it going” or “Dear Alice, you received this mail”), and

- This name is a nontrivial subsequence of their full legal name, and

- It is usually the first space-separated word in said full name (which contains at least 2 words).

There was this awesome post by patio11 that lists many more but focuses more on the software development side of it; but what I want to rant here is purely in everyday communications.

Since the title is “Synonymy”, I will only use Chinese names as examples, and limit myself to contemporary names of normal people (not literati-wannabes) that has native Hanzi names, excluding transliterated names from minor ethnical groups’ languages. Historically Chinese names consists of 姓氏名字号 (paternal family name, clan or lineage family name, given name at birth, chosen name, pen name) plus some titles, but that’s not why we are here today. Contemporary names of Chinese individuals usually consists of a surname (姓, paternal family name) and a given name (名). The surname is before the given name.

- The surname is usually inherited from one’s father. Statistically absolute majority come from fathers, with a mere 8% come from mothers. In People’s Republic, it is legally supposed to inherit from either mother or father, but can also be (1) from a senior lineal blood relative, (2) from a foster parent, or (3) anything with “other legitimate reasons” (Civil Code 1015). It does not change with marriage to match the spouse, so maiden name isn’t a thing (Civil Code 1056).

- Most surnames are one one syllable, like Wáng 王, Lǐ 李, Zhāng 张, Liú 刘, etc.. (Each syllable in Chinese is one character which shows as one square figure.)

- Some surnames are two syllables, like Ōuyáng 欧阳, Shàngguān 上官.. Out of 1.4 billion people in China, only <1.5million have bisyllabic surnames.

- The given name is usually chosen by one’s parents after birth but before obtaining a certificate of birth, so the timespan for coming up with a name is quite short. It can be changed with legitimate reasons.

Usually in China, people are addressed with their full names, especially among strangers. Most web forms has only one name field where people fill in their full name. If you receive a package delivery, the postal worker would call you by the full name. If a middle school teacher wants a student to answer a problem, they will use the full name. Sports broadcasters uses full names to talk about players (YÁO Míng is never addressed as Míng). The full name here essentially acts as a “first name”. And that’s why I want to be addressed as WÚ Yuè so hard.

Nicknames are another story. When addressing someone you already know, there are multiple possible options:

- Just use the full name! Many of my friends refer to me as WÚ Yuè with zero problems. This works especially well for 1+1 names (I will use x+y to denote names with x syllables in the surname and y syllables in the given name). But virtually every teacher I know addresses students as their full names. That’s also how students mostly call each other.

- Disyllabification – derive a nickname of two syllables from one’s name. Mandarin really likes even number of syllables due to its prosodic morphology.

- Option A: pick two syllables from one’s name. Address 1+1 names as is, and 1+2 names with only the given name part. My high school chemistry teacher really likes this. He calls me Wú Yuè, but if your name is Zhāng Xiǎosān, he will call you Xiǎosān. For 2+1 or 2+2 names, people usually just go for the two-syllable surname: I would address an Ōuyáng Zǐxuān with their surname only Ōuyáng.

- Option B: Add a prefix Xiǎo- (small-), Lǎo- (old-), or Ā- (just ah-, no real meaning) to one syllable in the name, usually the surname or the last syllable. If your name is Zhāng Mèngdié, then Xiǎo-Zhāng, Xiǎo-Dié and Ā-Dié all make sense; I have personally had people calling me Xiǎo-Wú and Xiǎo-Yuè; I’m not old enough for Lǎo-Wú yet but it makes sense.

- Option C: Reduplication. Repeat one syllable, usually from the given name, twice. If you call me Yuèyue (or even worse Xiǎo-Yuèyue), you are implying that I am 6 and/or you are my mom. This feels like toddler’s speech to me, but might be perfectly normal for some others.

- Nicknames can also be arbitrary. After all they are nicknames. My online friends call me 一团 based of “Etaoin”, my screen name.

This is very well contrasted to monolingual anglophones in America (and probably other Western cultures). For them, first name is for casual addressing, surname+title is for formal speech or writing, and full name is for angry parents to yell at their kids.

In a chart:

| Use case | What to use in US English | What to use in PRC Mandarin |

|---|---|---|

| Calling a close friend | First name / nickname | Full name / nickname |

| Calling a non-close-friend classmate | First name | Full name |

| Delivery person to identify a recipient | First name | Full name |

| Rideshare drivers to identify a rider | First name | Last 4 digits of phone number |

| Hospital, nurse calling patient into exam room | First name | Full name or appointment number |

| Starbucks, when ordering and picking up | First name | Surname and gender title |

| McDonalds, picking up | First name | Order number |

| Addressing a teacher / professor in formal writing | Title + full name | [Surname or full name] + [job title, e.g. “teacher”] |

| Addressing a teacher casually | First name | Surname + title |

In such a culture, asking people to address me with my full name breaks their expectation, and they are usually afraid of being perceived as yelling at me. Worse is that I don’t want to repeat this kind of explanation to everyone I meet, especially in the tertiary sector, so currently in the US I just come up with some random legitimate-looking first names for the ease of Starbucks baristas and Lyft drivers.

This also explains why a lot of Chinese people when coming to the US come up with generic-looking English names like Tom or Angelina; the counterargument of keeping their cultural identity in their names only results in misuse of such first names and more frustration.

Rant part 2: name as identification

Americans like to use one’s name as a form of identification. In a lot of police systems, people are identified with names and birthdates.

This simply doesn’t work with Chinese names. I am Wú Yuè, and I did my undergrad at PKU. Here are some top Wú Yuès in google; none of them is me:

- Yue Wu, associate professor at Pittsburgh

- Yue Wu, PhD student at CMU

- Yue Wu, professor at Iowa State

- Yue Wu, Director of Product at Lyft

- Yue Wu, computer vision scientist at Nvidia

- Yue Wu, faculty at U North Carolina. He also did undergrad at PKU.

- Yue Wu, PhD student at UCLA. He also did undergrad at PKU.

Many of them also work on CS related topics just like me. My personal website is therefore an SEO disaster.

On a personal level, I know four other Wu Yues throughout my pre-college education: one from kindergarten, one from middle school, one from high school, and another is a math teacher at my high school.

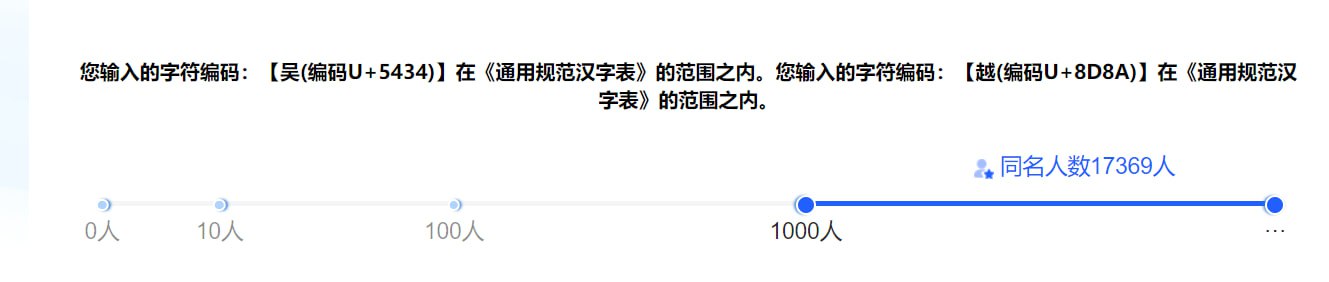

According to a Chinese government website, there are more than 17,000 people with the same name and spelling as me. If we consider homophones, there will only be more. Since 70 years is roughly 26k days, we can say that there is at least 0.5 Wu Yues getting born on an average day. There are 156k people named 王刚 Wáng Gāng in China, which means that every day there are a handful of them getting born. All of this is to show that “name+DOB” identification is useless. This is just another unrealistic assumptions on names that’s made because it makes sense in one society and one culture.

Conclusion

Names are weird. Please call me Wú Yuè (IPA [u˧˥.ɥœ˥˩]) next time when you want to just use Yue. And if you see someone online that goes by WU Yue then there’s a 99.994% chance it’s a different individual.